Earthworks and Mounds

Earthworks in Central Minnesota

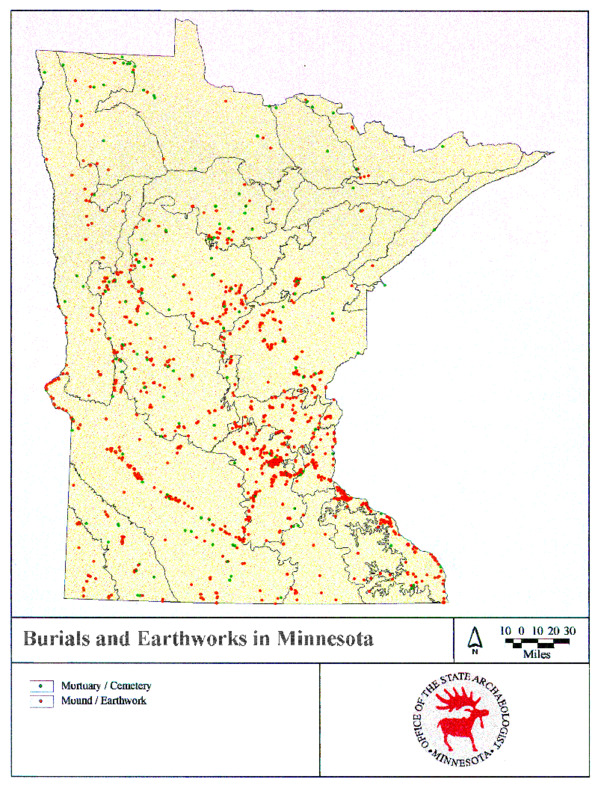

Mni Sota Makoce, the Dakota term for a region that includes Minnesota, is both historically and today, a Native space. This is evident in the Native earthworks which are spread across Stearns, Benton and Sherburne Counties. These earthworks consist of both burial and effigy mounds, and both have important historical and contemporary meaning for the ancient builders and their current relatives.

Burial mounds historically contained the remains of Native loved ones. In central Minnesota, the builders were mainly the ancestors of the Ojibwe and Dakota people. In Mni Sota Makoce, the authors describe the Dakota as, “the most prolific mound builders of Minnesota” (Westerman & White 2010, 32). These mounds were constructed in a deliberate and symbolic way, as resting places for the deceased loved ones of the Dakota (ibid). Burial mounds were usually built in round or linear shapes and are usually located along bluffs and terraces above bodies of water, such as rivers, lakes or streams.

Effigy mounds are large earthworks that formed figurative designs, such as fish, snakes, elk, or other animals. These mounds were believed to have been built for spiritual and burial reasons. This type of earthwork was not exclusively built near water or on bluffs, but like the burial mounds, they still had significant meaning.

One just needs to look at the historic maps of early Minnesota archeologists T.H. Lewis, J.V. Brower, or Newton Winchell to see the ancient burial and effigy mounds located throughout central Minnesota. In Winchell’s, The Aborigines of Minnesota, he presents several reports on locations of these mounds including one on an island in the Haha Wakpa (Missippi River) one mile below St. Cloud in Stearns County (Winchell 1911).

Sherburne County is the location of several mounds. As with most mounds, the mounds found in this county are on a bluff above the water. One of the two main mound locations is near the Elk River and is called the Moorhouse Mound Group. (Wilford 1969). These mounds were surveyed by Theodore Lewis in 1886, and at that time, there were twenty-six mounds at this site. The largest mound in this group was eighty-eight feet in diameter and fifteen feet tall. Bone fragments and artifacts were found in this group. Mound No. 19 is notable because it was three hundred and fifty feet long, eighteen feet wide, and two feet high. Bones were also found in this mound (ibid). There was also an effigy mound located in this Moorhouse group, which was shaped like a fish with a “bifurcated tail” (ibid. p10).

The other major mound group in Sherburne County is the Christensen Mound Group (Wilford 1969). Lewis surveyed this group in 1890, a few years after he surveyed the Moorhouse Mound Group. In this group, there was one main mound and twenty-nine small mounds. These were found near Elk Lake, and as a result of the soil there, they are all made of sand. Mound No. 1, as it was designated by Lewis, was eighty-two feet in diameter and fifteen feet high. The small mounds were mostly about thirteen feet long, and about two feet tall. There were animal bones, such as bear skulls and teeth, found in these mounds, along with some pottery.

As seen in Winchell’s map, mounds were not exclusive to Sherburne County. At one point most of central Minnesota had mounds dotting the landscape on ridges and bluffs along the Haha Wakpa (Missippi River). Although these earthworks deserve(d) respect, most, if not all of these mounds have been disturbed, excavated, or completely destroyed either by erosion or human activity. In the past, earthworks have been used for picnic grounds; “only a couple attended the picnic Sunday at the Indian mound at Rice lake” (Little Falls Herald 1907). The mounds have also been used as archeological sites; “an excavation of about six feet deep has been made into the side of the mound from where the bones were taken” (Little Falls Herald 1912). Many of the locations of these earthworks are now homes to bustling cities, residential neighborhoods and rural farmlands. But their importance to Native people has not changed.

The reports of early archeologists may be the only record of the existence of many of these earthworks but what cannot be denied is that their historical existence shows that Native people, particularly the Ojibwe and Dakota, inhabited this area of Mni Sota Makoce long before the Euro-American colonial settlers.

References

Arts, Joe Alan, Emilia L.D. Bristow, and William E. Whittaker. (1976). Mapping Precontact Burial Mounds in Sixteen Minnesota Counties using Light Detection and Ranging(LiDAR). Project, Office of the State Archeologist, University of Iowa, Iowa City: https://mn.gov/admin/assets/2013-Archaeological-Prospection-for-Precontact-Burial- Mounds-Using-Light-Detecting-and-Ranging-%28LiDAR%29-in-Scott-and-Crow-Wing-Counties%2C-Minnesota_tcm36-187248.pdf

Morrison County. Celebrating 150 Years. Original Historic Site No. 15. 2006.Westerman, G., & White, B. M. (2012). Mni Sota Makoce: The land of the Dakota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Wilford, L. A., Johnson, E., & Vicinus, J. (1969). Burial mounds of central Minnesota; excavation reports. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

Winchell, N. H., Brower, J. V., Hill, A. J., & Lewis, T. H. (1911). The Aborigines of Minnesota (pp. 220-345). N.p.: Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved from https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/56589