Native history and Fort Ripley

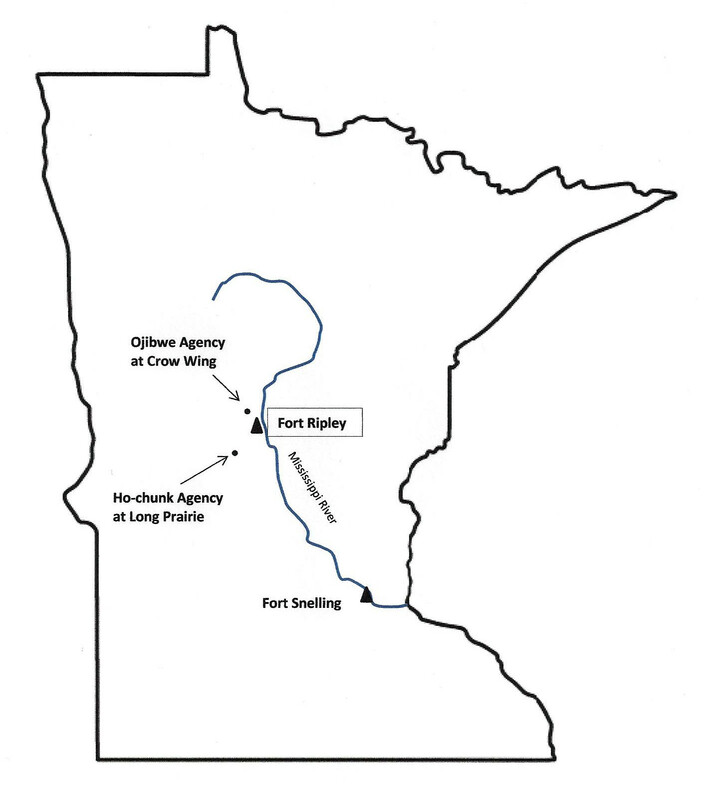

Native involvement in the history of Fort Ripley was not as widely understood as other forts and trading posts. The fort existed for a comparatively short time and it had no major settlements in the area. As a trading post, merchants and Indians tended to congregate at the post near the Crow Wing. However, the fort did function as a deterrent for potential hostile tribes in the area, thus protecting the settlers and merchantmen, extending American influence into the Minnesota frontier. Despite not having a military function, Fort Ripley was a major part in the power projection strategy of the United States of America.

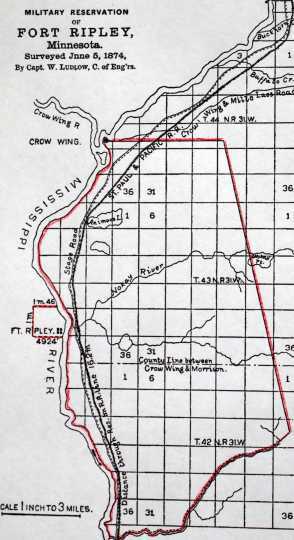

Fort Ripley was original established as Fort Gaines, but on November 4, 1850 it was redesignated as Fort Ripley. When it was established it replaced Fort Snelling as the northern most army instillation, there were multiple reasons for its establishment. One, to keep the Winnebago tribes from returning to their homelands in Iowa. Two, prevent the skirmishes between the Ojibwe and Dakota tribes in the area. From the perspective of the U.S. government, Ripley was established to protect the Winnebago from the unfriendly Dakota and Ojibwe tribes in the area. Instead of serving as the heroic fort on the frontier of an unsettled wilderness, Ripley mainly served as a post office and furnished business to local farmers and traders. The role as a main trading hub was assumed by the nearby Sioux Agencies.

Fort Ripley remained active until the Ho-chunk tribe was relocated out of Minnesota. When they left, the U.S. government saw no reason to keep the fort open. Ripley was evacuated on July 8th, 1857 after determining that the Chippewa were a peaceful people and after the Winnebago moved to South-central Minnesota. However, when the troops withdrew, the Ojibwe, still not wanting white settlers on their land, again resumed fighting for their land. Army troops soon returned to the area and Fort Ripley was again used as a deterrent to future Ojibwe “aggression”.

Like Fort Snelling, Ripley would never face an Indian attack, this did not end its involvement in Native American affairs though. Fort Ripley was the site of meeting between (Bagone-giizhig) Hole-in-the-Day, renowned chief of the Ojibwe, his two wives and the Chaplian of the fort in March of 1852. This meeting took the form of afternoon tea and they discussed the conversion of Bagone-giizhig (Hole-in-the-Day’s) tribe to Christianity. Later in the year, (Bagone-giizhig) Hole-in-the-Day and his wives would return to the fort to request a Christian burial for their son. At this time, the chaplain answered two questions the chief had for him. The first, whether it would be proper for him to have a feast in remembrance of his child? The chaplians answer was no. The second, how his two wives whom he intends to put away (divorced) should be treated? The chaplain answered, “He must see that they are comfortably provided for and protected, with the liberty of marrying again, when the obligation of support and protection would cease on their marriage, and that his children should have all the privileges of his family.”

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, the troops at Fort Ripley were replaced with volunteers. However, when the Dakota uprising started in southern Minnesota in August of 1862, troops were again sent to Fort Ripley. The Ojibwe were still believed to be peaceful, having passed on the opportunity to join Little Crow and the Dakota. John Johnson (Enmegahbowh), an Episcopalian deacon and chaplain at Fort Ripley, sounded the alarm at Gull Lake that the renowned chief Hole-in-the-Day was going to push the settlers out of their lands and march on to St. Paul. Reinforcements from Fort Ripley were requested by Lucius C. Walker, an Indian agent at the Chippewa agency sent by courier. August 19th, a small detachment of a dozen soldiers was dispatched from Fort Ripley to the village of Hole in the day to arrest him. At the time of the uprising, Fort Ripley had only about 30 soldiers stationed there.

January 1877, the laundry, commissary, and officers’ quarters were destroyed in a fire. The fort was deemed not important anymore due to the Indian problems being mostly resolved so the fort was closed instead of repaired. By summer 1878, the fort was officially abandoned. Today, the only remains of the old Fort Ripley are part of the powder magazine, ironically, this was the place where they stored gunpowder and other explosives.

Today, the Minnesota National Guard has approximately 180 or 1.4% of the Soldiers and Airmen identify as Native American. According to LTC Merricks, Director of Diversity and Inclusion for the Minnesota National Guard, “the leadership at Camp Ripley participates in a tribal consultation with the Minnesota Federally Recognized Native American Tribes. The purpose is to consult with Native American Tribal representatives to address potential concerns regarding ancestral territories and burial sites. Consultation is required to occur during the planning stages of any federal undertaking to determine if there will be an adverse effect to Native American sacred sites, burial sites, or archaeological sites. Yearly face to face consultations have been used as an efficient and expedient method to inform Tribal representatives of Minnesota National Guard proposed and completed projects and to allow for Tribes to voice any concerns.”

The history, as well as the futures of Minnesota tribes and Camp Ripley remain intertwined. A relationship that was founded on mistrust and hostility, now is one of inclusion and cooperation. Both parties assisting and benefiting from the other.

Works Cited:

Prucha, F. Paul. "Fort Ripley: The Post and Military Reservation." In Minnesota History, 205-24. 3rd ed. Vol. 28. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1947.

Tanner, George C. “History of Fort Ripley, 1849–1859: Based on the Diary of Rev. Solon W. Manney, D.D. Chaplain of this post from 1851 to 1859.” Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 10, pt. 1 (1905): 179–202.

Diedrich, Mark. "Chief Hole-in-the-Day and the 1862 Chippewa Disturbance: A Reappraisal." Minnesota History 50, no. 5 (Spring 1987): 193–203.

Merricks, Jeffrey W. “Information Request.” Information Request, 11 Dec. 2018.

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 2, Minnes. Hist. Soc., 1961.

Prucha, F. Paul. “Fort Ripley: The Post and the Military Reservation.” Minnesota History 28, no.3 (September 1947): 205–224.