Founding of St. Cloud State University

Mni Sota Makoce, the Land Where the Waters Reflect the Clouds, was the original place name given to the territory that encompasses and extends beyond the boundaries of Minnesota. This name was used by it’s original inhabitants, the Dakota. Up until the mid-1600s, when French Jesuits and traders first began exploring this territory and producing documents of their travels, the Dakota had already been occupying this area for thousands of years. One would only have to travel to the Jeffers Petroglyphs site in Southwestern Minnesota to see physical evidence of a Native presence that dates back over 7,000 years (Sanders, 2014).

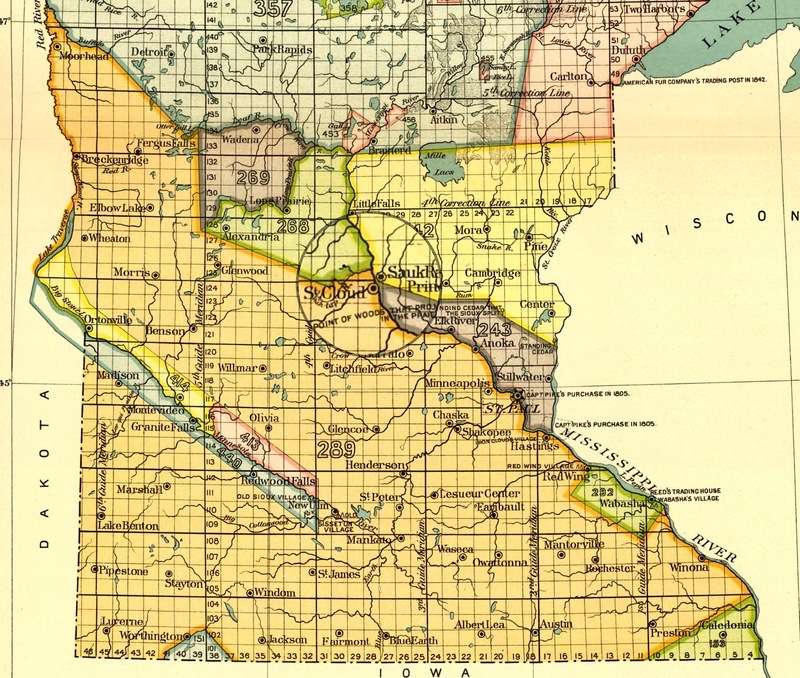

Fast-forward to 1825, where, after more than a thousand generations of inhabitance, Dakota cultural identity has now become synonymous with the land of Mni Sota Makoce. During the summer of 1825, U.S. government officials met with Dakota and Ojibwe delegates--as well as other delegates from surrounding Tribal Nations at Prairie du Chien, with the intent of drawing boundaries that would divide the region among the groups attending. The strategy was to assign the area discrete ownership to specific tribes, which would later ease the way for the acquisition of the land through Nation-to-Nation treaty making. Although many tribal leaders rejected the idea of land boundaries, expressing a philosophical disconnect regarding the concept of land ownership, the treaty was signed by the parties as a result of U.S. pressure, and a willingness to retain peace between all parties. There were no formal land cessions in this treaty; however, in effect, it was a cession of land for the Dakota, who lost claims to the northern parts of their traditional homelands. The treaty assigned much of the southern portion of the state to the Dakota, while the Ojibwe were assigned much of the north (see 1899 map).

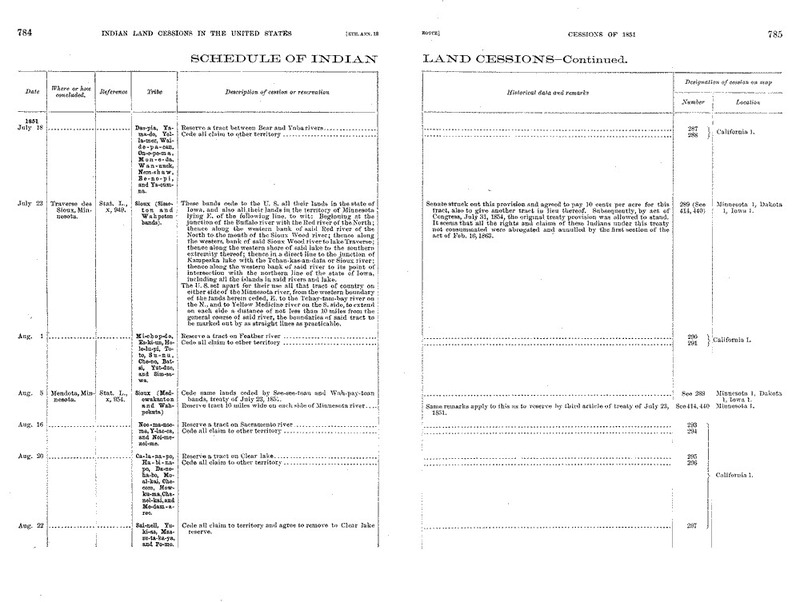

The majority of St. Cloud, including St. Cloud State University's campus, was on Dakota-assigned land, as the Mississippi River acted as the border in this region between Dakota and Ojibwe-assigned land. Prior to the 1825 treaty, this land was recognized as the, “middle ground,” an area that was shared between the two (Westerman & White, 2012). In 1849, Minnesota became a territory, and with it soon followed growing tensions between Native communities and encroaching white settlers who were dramatically increasing in numbers. The city of St. Cloud was eventually obtained by the U.S government in 1851 through treaties signed at Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. These treaties were later abrogated after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, a direct result of the U.S. government failing to provide annuities promised in the prior treaties.

After the 1851 Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota concluded, the Dakota were confined to two small reservations along each side of the Minnesota River and a larger reservation along Lake Traverse. With the Native people removed, the White settler population of the Minnesota Territory increased rapidly, from 6,077 in 1850 to 125,000 in 1856 (Cates, 1968). White settlers recognized great value in the lands previously held by the Dakota and Ojibwe. The fertile soil, abundant timber, rolling meadows, and plentiful lakes and streams were attractive to land speculators and homesteaders. The area that became St. Cloud was ideally positioned along the Mississippi River, and became a frequent crossing point for those traveling to and from St. Paul.

In light of the growing population, Minnesota became the 32nd U.S. state in 1858. Education of its citizens became a priority for the state. Since territorial law had provided for free common schools open “to all persons between the ages of four and twenty-one years,” competent teachers were in high demand, especially in rural areas. The first Minnesota Legislature addressed the need for teacher training by establishing a normal school system (Carmichael, 1954, p. 93). The first, second, and third State Normal Schools were established in Winona (1860), Mankato (1868), and St. Cloud (1869). The State Normal School Act of 1858 mandated that each city must raise $5,000 to help fund land acquisition, building construction, and faculty salaries for the school. Bonds were sold in St. Cloud to raise the $5,000. Once this requirement was met, the state matched that amount to provide $10,000 for the school (Cates, 1968).

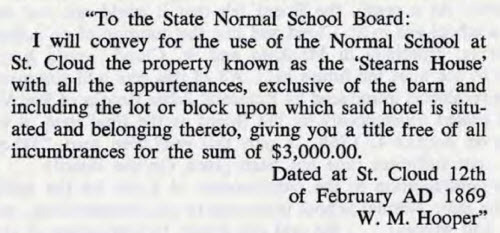

The State Normal Board considered four locations for the St. Cloud Normal School. Their selection was based on “the natural beauty of the location, situated on a high bluff overlooking a vast sweep of the Mississippi River...and the presence of a building on the site which could temporarily house the new school after sufficient remodeling was accomplished,” (Cates, 1968, p. 13). The Stearns House, which had operated as a profitable hotel prior to the Civil War, and six acres of land were purchased from W. M. Hooper for $3,000. When the school opened in 1869, the Stearns House accommodated for classrooms on the first floor, a model school on the second floor, and a women’s dormitory on the third floor. Ira Moore was the school’s first principal, and the first enrollment included sixty Normal students and one hundred Model students (demonstration students in elementary grades). A second building, Old Main, was built in 1874 for $60,000. The building increased the Normal student capacity to 250 and was said “to be one of the best, in design and construction, for the purpose in the west” (Williams, 1881, p. 382).

Over its history, St. Cloud State University has been renamed by the Minnesota State Legislature several times. Former names include the Third State Normal School (1869-1873), the State Normal School at St. Cloud (1873-1921), St. Cloud State Teachers College (1921-1957), and St. Cloud State College (1957-1975). Even today, St. Cloud State University draws students to campus by highlighting its beautiful location “between downtown St. Cloud and the Beaver Islands, a group of more than 30 islands that form a natural maze for a two-mile stretch of the Mississippi River,” (St. Cloud State University, 2017).

When acknowledging the foundation of St. Cloud State University, or any other institution within the State of Minnesota, one must always begin with the Dakota. Although this aspect is far too often overlooked, St. Cloud State University resides within Mni Sota Makoce, the lands that collectively shaped Dakota language, political structure, spirituality, and traditional values over several millennia. The campus sidewalks we travel daily and the spaces we learn in, contain the spirit of this culture--a characteristic that cannot be escaped, destroyed, or otherwise terminated. In this regard, St. Cloud State University, at its most fundamental identification, will always be a Dakota place so long as it continues rest alongside the Mississippi in the Land Where the Waters Reflect the Clouds.

References

Carmichael, O. C. (1954, Autumn). The roots of higher education in Minnesota. Minnesota History, 90-95.

Cates, E. (1968). A centennial history of St. Cloud State College. Minneapolis, MN: Dillon Press. Retrieved from https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/archives_univpubs/1/

Sanders, T. (2014). Jeffers Petroglyphs: A recording of 7000 years of North American History. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved from https://sites.mnhs.org/historic-sites/sites/sites.mnhs.org.historic-sites/files/docs_pdfs/Jeffers-Petroglyphs-%20history.pdf

St. Cloud State University. (2017). About St. Cloud State. Retrieved from https://www.stcloudstate.edu/about/default.aspx

Westerman, G., & White, B. (2012). Mni Sota Makoce: The land of the Dakota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

Williams, J. F. (1881). Outlines of the history of Minnesota. In History of the upper Mississippi Valley. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Historical Company.