Indian Boarding Schools

In the late nineteenth century, military, missionary, and government officials advocated for the removal of Native American children to residential boarding schools which would erode their Native identities in order to "civlize" them through an expanded education in the English language, Christianity, and American (White) culture. Many children were forcibly removed from their homes and communities to attend these distant schools. Over the history of boarding schools in the United States, some students would choose to attend and some would be forced. Many parents thought by sending their kids to these institutions, they would have more opportunities by gaining skills valued by the dominant society.

The first boarding school opened in 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and was located in Pennsylvania, under the authority of Richard Henry Pratt. Pratt was very blunt in the school’s work as he stated, “Our goal is to kill the Indian in order to save the man.” Many of the children in the boarding schools found this to be true. The boarding schools were not concerned with the education of the Indian children, but rather were concerned with assimilating the American Indian youth in an effort to kill off their culture. (Treuer, 2012)

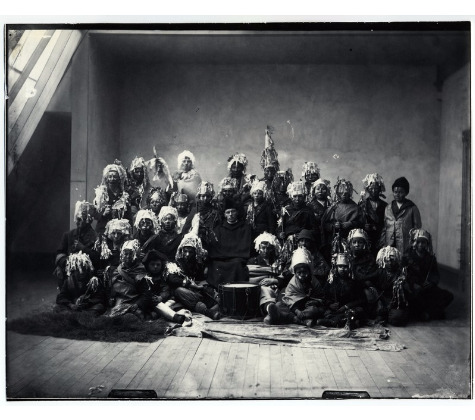

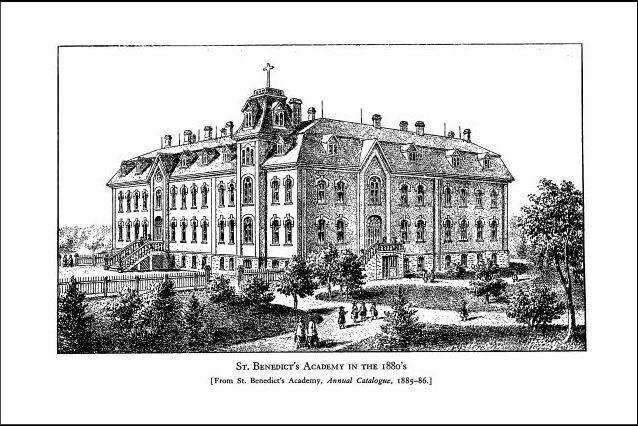

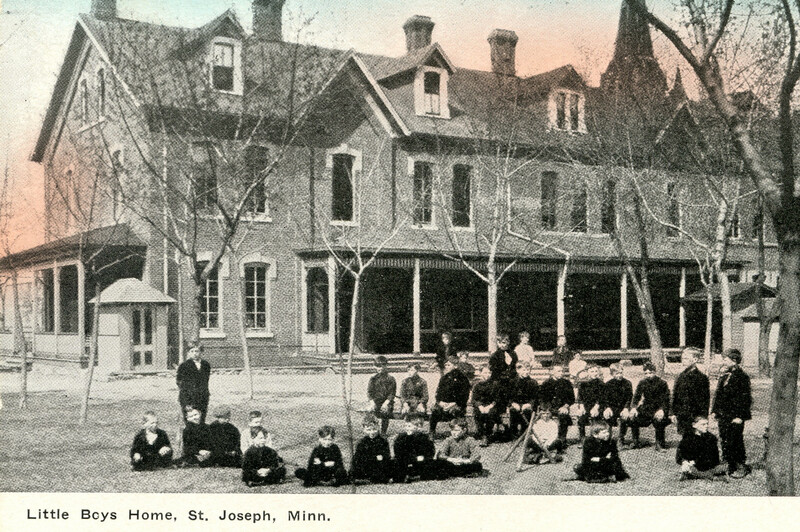

Sixteen boarding/mission schools were created in Minnesota. The earliest mission school in Minnesota was the White Earth Indian School which was established in 1871. The boarding schools located closest to the St. Cloud area were St. John's Industrial School for Chippewa Indian Boys and St. Benedict's Industrial School for Chippewa Indian Girls. These boarding schools were built as part of St. John's University and St. Benedict's University. In 1885, Abbot Alexius traveled to St. John's with fifty Native American boys and they were placed under the charge of Fathers Chrysostom and Meinrad and Brother Phillip Killian. The Government contract allowed fifty Chippewa boys to be trained at St. John's, and fifty girls to be trained at St. Benedict's. (Worship and Work, page 175, 2015)

The government’s Indian Bureau hoped that these Native children would learn to adopt the patriarchal system that dominated the culture in the United States. These boarding schools primary objectives were for young Native Americans to abandon their traditions and convert to Christianity. The ages of the children were from nine to fifteen years old, they were to be taught in elementary level education, along with a job skill. Typically classes would last half a day. These industrial schools prepared boys for manual labor and farming. The girls were trained to do domestic work (Lajimodiere, 2016). Some of the job skills for boys that were taught were printing, tailoring, shoemakers, and carpenter skills, cooking skills, blacksmithing and gardening. Girls were taught dress making, plain sewing, crocheting, mending, laundry, knitting and darning. A religious program was also mandatory. (St Johns Archives, page 176, 2015)

The mission of these boarding school was to reconstruct Native American children’s minds, and personalities by severing children’s physical, cultural, and spiritual connections to their tribes, and also disconnecting them from their cultural identity (Lajimodiere, 2016). During the process of this reconstruction, Native American children were exposed to experiences that affected their mental and physical health. If parents would not send their children to these boarding schools, the Indian Bureau of Affairs would withhold rations, clothing, and other annuities (Lajimodiere, 2016). If parents resisted, they could be jailed (“Indian Boarding Schools”). Parents and families were also harmed by these boarding schools.

At St. John’s boarding school, boys were forced to dress like girls for a whole month, and young girls would have their hair cut short as punishment at St. Benedict's. At St. Benedict's one student remembers “being made to chew lye soap and blow bubbles that burned the inside of her mouth” (Lajimodiere, 2016). This was a common punishment for students if they spoke their tribal language. One sister at St. Benedict’s was asked about what types of punishments were given to students at the Industrial school at that time. She said, “Oh, they would have been given a timeout to reflect on their behavior.” When she was told about another student's recollection of abuse that was going on at the boarding school, the sister responded, “Oh, no, that is so horrible, just horrible, I can’t believe they did that, but that was so long ago.” The sister than said, “I know that there were a lot of horrible things that took place back then to the “Indians” and although we personally did not do these horrific abuses, we at St. Benedict’s have been working with the local tribes to try and make things right, for all the wrong that the Indians received while in the care of St. John’s and St. Benedict’s.”

After the Native American children went through the arrival process, they were told they could not speak their tribal language and were only allowed to speak English. Many Native American children ran away for a variety of reasons including homesickness and the harsh conditions at the boarding schools. Children sometimes would report to their parents on the conditions at the boarding school, and some parents traveled to the schools to attempt to remove their children. (St. John’s Archive, page 176, 2015) It wasn’t uncommon for children to become ill while at the boarding schools. There were five young Native American boys that died at St. John’s and you can find their burial sites at the school's cemetery. (St. Johns Archives, page 176, 2015) Their cause of death is unknown. The children found it difficult to be kept indoors. When spring came along, it was not uncommon for a few students to run away.

The lives of the Indian children who went to these boarding schools were dramtically changed. Being forced to assimilate to Western ways undermined their community and family identities. Through the "Americanization" process, part of their cultures and traditions were lost and these losses impacted future generations of Native people. Located just outside St. Cloud, these schools have also impacted the greater St. Cloud community because we, as residents, continue to live in a Native place where our Native history is often unknown.

Sources:

Worship and Work. (n.d.). Page 175. Retrieved May 01, 2017, from http://cdm.csbsju.edu/cdm/ref/collection/SJUArchives/id/11072

Worship and Work. (n.d.). Page 176. Retrieved May 01, 2017, from http://cdm.csbsju.edu/cdm/ref/collection/SJUArchives/id/11164

History of Survivance: Upper Midwest 19th-Century Native American Narratives. (n.d.). Retrieved May 01, 2017, from https://dp.la/exhibitions/exhibits/show/history-of-survivance/reservation-era/boarding-schools

http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/33/v33i02p053-060.pdf

Hoffmann, A. (n.d) St. John's University, Collegeville, Minnesota: A Sketch of its history. Available from http://www.csbsju.edu/documents/sju%20archives/hoffmann.pdf

Lajimodiere, D. K. (n.d.). American Indian Boarding Schools. Retrieved May 01, 2017, from http://www.mnopedia.org/american-indian-boarding-schools

Indian Boarding Schools. (n.d.). Retrieved May 01, 2017, from http://www.usdakotawar.org/history/newcomers-us-government-military-federal-acts-policy/indian-boarding-schools

Treuer, A. (2012) Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask. Borealis Books. St, Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.