Indian Boarding Schools at the College of St. Benedict and St. John's University

In the late 19th century, after the placement of reservations, the United States government implemented the use of Indian boarding schools as a tool of assimilation, taking children from their families on reservations and placing them into isolated facilities, transitioning them away from their culture. While some parents thought this would benefit their children, others were forced to give up theirs with threats including jail time and food rations. During their stay in these boarding schools, also known as industrial schools, some children lost their lives due to sickness. The adolescents who were able to come home were often unable to recognize their own parents or language (Treuer 2010).

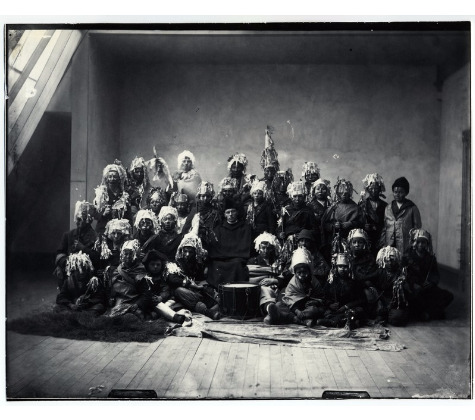

In 1884, the St. Benedict’s School for Chippewa Indian Girls opened in St. Joseph, Minnesota. This vast piece of land held a building 48x60 feet, three stories high, and was made of solid brick. The U.S. government issued a contract for 30 girls on March 19th, 1884. Then on January 1st, 1885 there was an added contract for 20 more girls. In August of 1886, the next contract was increased to 105 girls. All of these contracts required girls from the White Earth Reservation. The goal of this industrial school was to educate young Ojibwe girls for the Christian way of life learning history, reading, math, geography, etc., and what is necessary for a woman to know, such as sewing, knitting, preparing meals, and cleaning. The school burned down in April of 1886, however, a new building was completed to hold 125 girls (St. Benedict’s Industrial School at St. Benedict’s Academy St. Joseph, Minn. 19).

"The nuns and the priests and the Indian agent; they came and they took me and my brother away in 1934. My mom, she tried to resist, but if you do that, you’re going to go to jail. And it happened to some other people there in my generation; some of the parents went to jail" (Indian Boarding Schools 2017). For many families who lived too far from these schools, they were forced to give their children up. This caused much heartbreak, not only for the families, but for the children. They would be uprooted from their homes where they know they are safe and placed into facilities foreign to them.

The St. John’s industrial School for Chippewa Indian Boys opened on January 1st, 1885 in Collegeville, Minnesota. The school received 50 boys from White Earth Reservation, on a contract with the government through the Catholic Indian Bureau at Washington. The school was originally planned to be at St. Alexius Priory, Todd co., Minnesota, but Abbott Alexius, who was in charge of the industrial school, decided that St. John Abbey was better for the accomplishment of his projects (St. John’s Indian Industrial School 1975, p.113). The school’s mission was “ to carry out the best intentions of the government in the work of civilizing its wards and making them self sustaining and worthy citizens of a great country” (Catalog of St. John’s industrial school for Chippewa Indian Boys Collegeville, Minn. p.3).

Shortly after its opening, the Abbot realised his enthusiasm was not shared by all the boys and their parents. Three boys ran back to White Earth and informed the community of what the Abbot referred to as “a lot of lies”. Regardless a good number of parents took their children home and only twenty-four boys were left, out of original fifty boys (St. John’s Indian Industrial School, 1975, p.113). Every spring, a good number of them ran away, unable to bear life at the institution (Colman, 1956, p.147).

One of the rules of the school was “pupils are required to engage in actual labour upon the lands or workshops of the institution so that they may become useful members of society” (Catalog of St. John’s industrial school for Chippewa Indian Boys Collegeville, Minn. pg. 4). In an interview, a former student of St. John’s industrial school describes his schedule. Mr. John Morrison, a member of White Earth, attended the school from 1885 to 1886.

The day began with mass. At 7:00 there was breakfast, followed by catechism. At 8:00 am the boys were sent to the various shops to help with work-- carpentry, butchering, tailoring, in the shoe-shops, and gardening. From 11:30am until 12:30pm, dinner was provided and there was free time. 12:30--classes in reading, writing, arithmetic until 4:00pm. Supper was at 6:00pm. where there was always plenty to eat.

Mr. Morrison recalls how the teachers were not trained to teach and spent more time learning Chippewa from the boys than teaching them English. While there was no playing ground, the boys had recreation at 4:00 pm and played baseball and/or rugby. The boys had to get the wood used to heat their rooms, as well as, sweeping and scrubbing their buildings. After 7:30 pm, they were not allowed to talk until the next morning at mass. He also mentions the fear the boys felt towards their teachers because they had bad tempers and could lash out anytime (Pruth, 1956 para. 4).

Discipline was very strict and they were often whipped for trivial matters. Coming from households where they were never struck, the boys deeply resented this treatment. Mr. Morrison recalls an incident where a student was whipped and sent packing with no money or food on a cold morning. Mr. Joseph Omen, another student of the industrial school, recalls one boy getting six whipping in a day. He also states that they were constantly living in fear.(Fruth 1956, para. 4,6). The boys were often sick. Five boys died in the first five years (Colman 1956, p.147).

Even though applications to the school the reduced, with the government’s help, they were able to get a total of one hundred and fifty students annually from 1890 to 1896. Funding the school was now the problem and played a role in why the school was closed. By 1896, St. John’s school for Chippewa boys sent all the boys back to reservations (St. John’s Indian Industrial School 1975, p.119). The school operated for eleven years but did enough damage to last generations. From the late 19th century to the mid 20th century, many indigenous families experienced agony and torment as their children were sent away to industrial schools. Some would never see their children again, due to the actions of Congress and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. While this can be seen as a dark time in the history of the United States, it is important to recognize the past in order to not repeat history.

REFERENCES:

Catalog of St. John’s industrial school for Chippewa Indian Boys. (1888-89). Collegeville.

Colman, B. J. (1956). Worship and work: Saint John's Abbey and University, 1856-1980.

https://books.google.com/books?id=FpTSBIu05QoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=chippewa&f=false

Indian Boarding Schools. (n.d.). Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://www.usdakotawar.org/history/newcomers-us-government-military-federal-acts-policy/indian-boarding-schools

Interviews with the Reverend Alban Fruth, O.S.B, 1956

St. Benedict's Industrial School at St. Benedict's Academy, St. Joseph, Minn.file:///C:/Users/AMGOD/Downloads/SKM_C45818110715330.pdf.

Skjolsvik, O. (1957, April). "St. John’s Indian Industrial School." The Scriptorium 16(1): 111-123. Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://cdm.csbsju.edu/digital/collection/SJUArchives/id/26392/rec/292

Treuer, A. (2010). The people of Minnesota: Ojibwe In Minnesota. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.